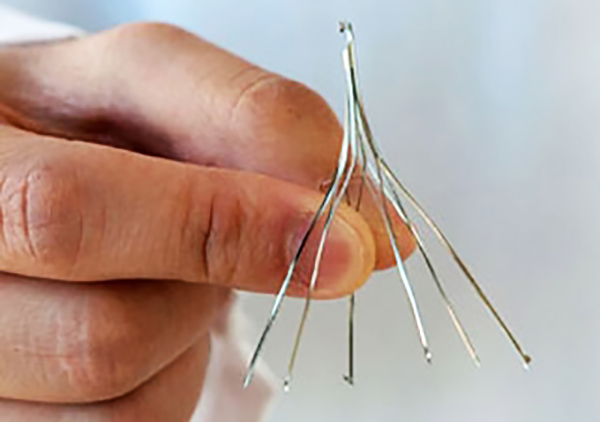

Medical device manufacturers C.R. Bard and Cook Medical are facing a growing number of lawsuits over their inferior vena cava (IVC) filters, which have been implicated in dozens of serious injuries and even deaths. These spider-like devices are implanted into a major vein running into one of the heart chambers, and were intended to prevent blood clots traveling from the leg and entering the pulmonary system, thus causing an embolism. Instead, these filters have been falling out of place, after which they migrate and fracture, allowing small metal fragments to travel into the heart and lungs.

What physicians and patients have not been aware of is how often these IVC filters fail.Drugwatch reported on a recent study, putting the risk of the Cook IVC Filter fracturing and puncturing a major blood vein at 43%. However, the news may be worse than that. Dr. Shezad Malik of Dallas, Texas, has the distinction of holding degrees and licenses in both medicine and law. In a recent article written for The Legal Examiner, Dr. Malik reports that IVC filters across the board have extremely high rates of failure. According to Dr. Malik, medical experts say that every IVC filter will eventually fail if left in place for a sufficient amount of time. The longer these devices remain in the patient, the greater the chance of injury and death.

IVC filters were intended to be a temporary measure for patients at risk for embolism who could not be treated with anticoagulant medications (“blood thinners”). In the spring of 2014, the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning to physicians that IVC filters should be removed as soon as possible, once the patient was no longer in danger of suffering a pulmonary embolism. Under no circumstances should they be left in place more than eight weeks beyond that point. According to plaintiff mass torts firms, such as Levin Papantonio, neither C.R. Bard nor Cook provided doctors with adequate warnings on this issue.

As if all of this were not bad enough, the Journal of the American Medical Association reports that in 8% of cases, IVC filters were useless in preventing pulmonary embolism.

It makes one wonder how and why the FDA gave approval to these devices in the first place. In the case of C.R. Bard, it may have been criminal fraud. In 2004, Bard hired an outside physician, Dr. John Lehmann, to evaluate its IVC filter for safety. When Lehmann reported the IVC filter to be dangerously defective, company executives simply buried the report. It was never submitted to the FDA as required by federal law. Although this report was recently uncovered by NBC News, courts in several states today are barring the “Lehmann Report” from being entered into evidence. On top of this, a regulatory specialist at Bard in 2005 refused to sign off on an FDA application for the device on grounds that it was poorly designed and prone to fracturing. A company executive simply forged her signature.

Even though the FDA has attempted to sound the alarm about IVC filters, the federal regulatory agency also bears some responsibility. The IVC filter was rushed through the approval process, using what is known as 510(k) Clearance. This is literally a regulatory short cut. If a drug maker or the manufacturer of a device can demonstrate that the product for which they are seeking approval is “substantially equivalent” to a similar product already approved and currently on the market, approval for that product is “fast-tracked.” The legislative intention, ostensibly, was to speed potentially life-saving drugs and devices to market for the benefit of patients.

Unfortunately, it hasn’t quite worked out that way. As a result, too many defective drugs and devices have been injuring and killing patients. Furthermore, evidence in these cases demonstrate that time and again, the manufacturers were aware of the risks associated with these products. However, in the great tradition of Corporate America, the accountants run the numbers and the executives decide that a few hundred million in fines and judgments – as well as a few human lives – are just part of the cost of doing business (and these fines and judgments are actually written off on company tax returns).

Until the profit motive is removed from health care in the U.S., we can expect more of the same.