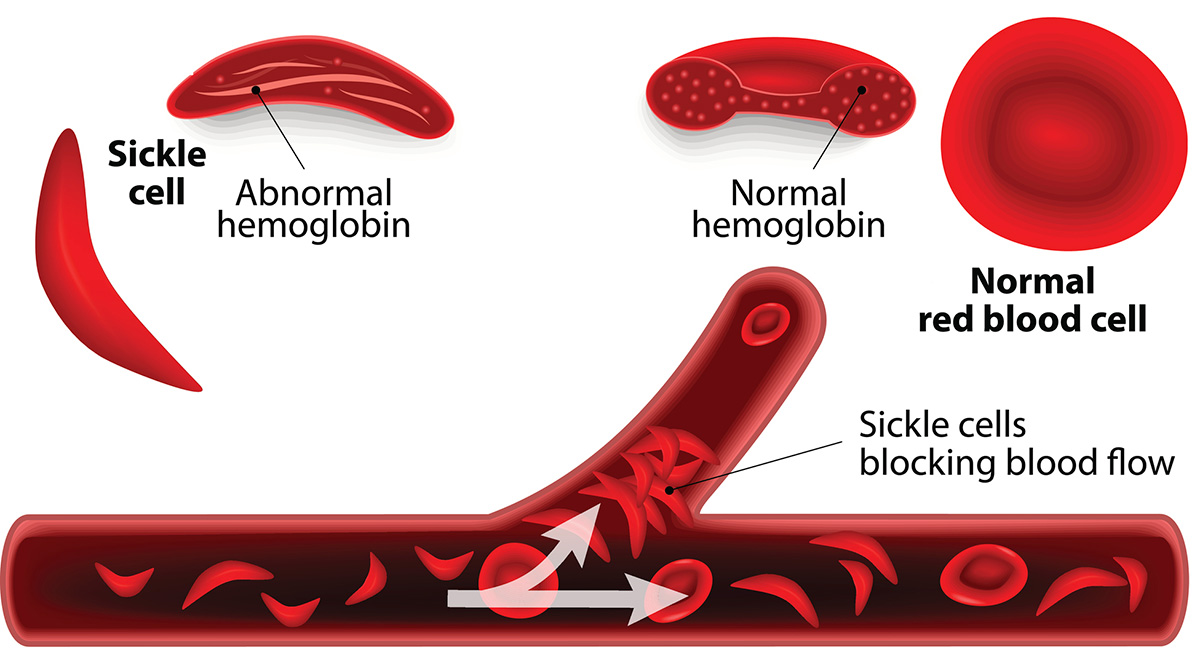

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is a relatively rare, genetic blood disorder that primarily affects people of African ancestry. Red blood cells, which are normally donut-shaped, become rigid and sickle-like. The result is anemia, swelling of the extremities, bacterial infections and impeded blood flow that can lead to stroke.

A patient who suffers from SCD is subject to “attacks” (known as a vaso-occlusive crisis or VOC), which can be caused by any number of factors, including changes in the weather, stress, and dehydration – and these attacks can be extremely painful. The good news is that a new, non-narcotic treatment for the pain associated with VOC is on the horizon after many years of delays. That sad part is that the delays have been caused by suspicion and mistrust by those who would be ideal candidates for clinical trials – a legacy of America’s history of racism.

Historically, African-Americans have good reason to distrust medical researchers. Throughout American history, blacks have been subjected to medical “experiments” without their full knowledge or consent. The most infamous of these was the “Tuskegee Syphilis Study,” which began in 1932 and involved 600 black sharecroppers – 400 of whom were infected with the venereal disease. They were not informed of their condition, being told only that they were being treated for “bad blood.” They were not given any treatment, even after penicillin became available in the 1940s. Subjects were simply observed as they died slowly from the long-term effects of the illness, which included blindness, insanity, and paralysis.

It was neither the first nor the last such experiment. During the mid-19th Century, one Dr. J. Marion Sims, still considered by some to be the “father of modern gynecology,” performed numerous experimental surgeries on slave women without anesthesia. Although anesthesia was new to the medical profession in the 1840s, it was available – but Sims chose not to employ it on his subjects, telling medical students years later that his procedures were not “painful enough to justify the trouble.”

Even the 21st Century saw racism come into play during medical research. In 2014, revelations came out about a measles vaccine under development at the Centers for Disease Control. It turned out that black children given the vaccine at the age of three years or younger were at 200% greater risk of developing regressive autism. However, parents of the children involved in the study were not informed of this risk.

These are only three examples of many representing “medical apartheid” in the U.S. over the past 180 years or so. Although many of these have been forgotten by most of society, the African-American community has a long memory. Even today, many black Americans are hesitant to seek out necessary health care services when needed – and are even more reluctant to volunteer for medical studies.

Small wonder that even though development of the new VOC drug known as rivipansel began almost a decade ago, it has taken until now to find enough volunteers to carry out a Phase 3 clinical study.

The companies involved in the development of rivipansel, GlycoMimetics and Pfizer, have been doing educational outreach and have hired advocates in order to facilitate communication across cultural lines. While these efforts have resulted in some success, there is a great deal of history to overcome and trust that needs to be re-established.